The ECB’s constant failure in forecasting and delivering inflation close to 2% is revealing an important crisis of thinking in the ECB’s policy making. 20 years after the creation of the euro and 10 years after the burst of the financial crisis, it is time to take reflect on how monetary policy should work in the future, by carrying out a comprehensive review of the monetary policy strategy of the European Central Bank.

The European Central Bank was created in the good old days of central banking – when it was boring and simple. In 1998, central banks had one job to focus on: to maintain the rate of inflation below a certain threshold (say 2%) by using essentially two instruments: setting the key interest rate and buying assets through open-market operations. This way, central banks could control the price of money in financial markets, and thus, indirectly influence the quantity of money circulating in the economy.

This simple model proved to work rather well. Until 2008, inflation was indeed very stable, to the pride of the ECB.

Since the great financial crisis, however, the ECB has had a much harder time to achieve its mandate. In fact, for the six past consecutive years, the ECB has missed its inflation target. And this, despite having deployed an armory of “unconventional” policies and strategies: negative interest rates, quantitative easing, TLTROs, forward guidance…

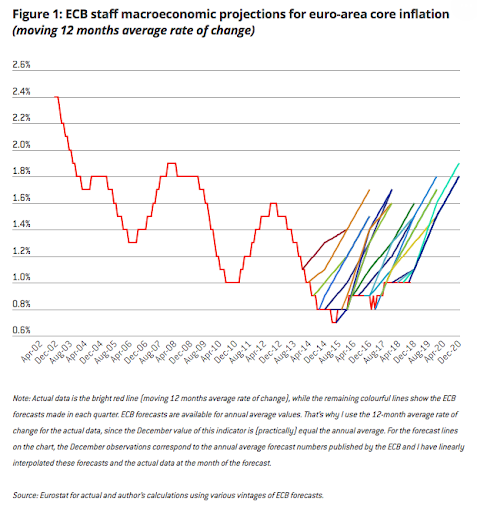

Not only the ECB failed to lift inflation up to 2%, but it has also failed consistently in predicting inflation forecasts. As the chart below shows the ECB’s inflation forecasts have been embarrassingly over-optimistic for too long.

Source: Bruegel, 2018

The reasons why inflation is so low is the subject of intense academic debate.

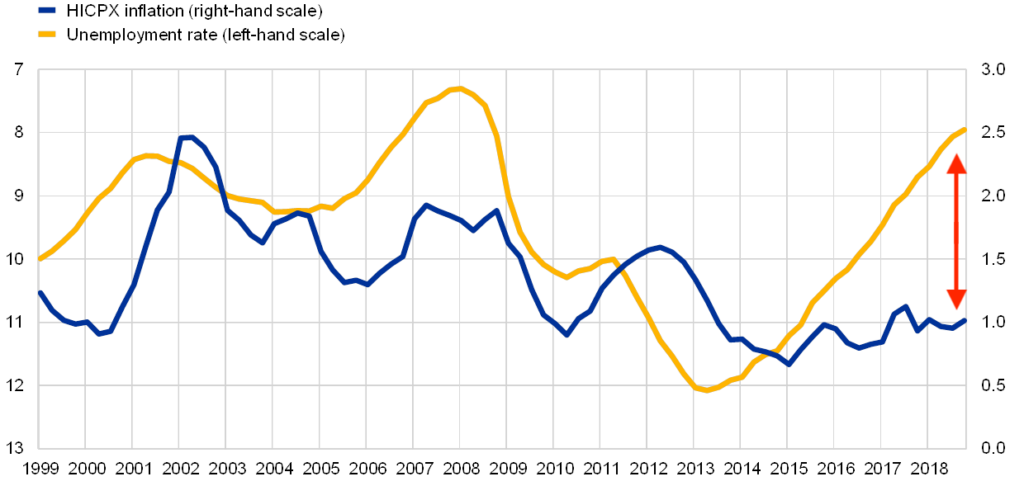

Perhaps one of the most heated points in this discussion is the so-called Phillips’ curve, which describes the (supposedly) natural correlation between unemployment and inflation. In a normal world, inflation would start soaring as unemployment goes down because workers can more easily bargain for wage increases when unemployment is low, which drives consumption. But today, this correlation seems to be broken.

But the ECB seems to think this relationship is just temporarily muted. For example, ECB Board member Benoit Cœuré has advanced the so-called “hysteresis“ hypothesis: the idea that the symptoms of the crisis are still impacting the economy even though their causes have disappeared. In other words: the low inflation is just a temporary phenomenon which does not require rethinking the old paradigm.

Source: ECB Bulletin, June 2019

However, more powerful and unprecedented deflationary pressures could be at play. For example, technological progress is inherently pushing down the cost of many production processes, but this is not always well reflected in final prices. This factor is somehow taken into account in the statistical process, but it could be largely underestimated. Another external factor could be the globalization of the labor market, which means the labor force in Europe is now competing with the ones from emerging market economies: because today companies can so easily outsource their labor force elsewhere across the World, this means they can expand their production capacity without increasing wages or hiring more people locally. Similarly, the precarisation of the labor market, with the rise of low-paid, part-time jobs is also undermining the ability of workers to bargain for better wages. Finally, experts also argue that weak domestic demography in many European countries also has a deflationary impact.

While academics are debating those fundamental trends, central banks remain confident that those are not the main reasons for the low inflation environment. Moreover, they argue that whatever is the cause for the low inflation, the policy response lays outside from the monetary policy realm. Namely, we need a more active fiscal policy stance to better accompany and transmit the limited policies of the ECB. After all, with quantitative easing and negative interest rates, the ECB has done all it could, at least so they think.

Of course, history might prove them right as inflation might eventually go back to normal. And still, the current response by central banks is not satisfactory in our view.

The only limits to monetary policy are timidity and lack of imagination

First, the idea that central bank policies have reached their limits and that only fiscal policy can now help is theoretically untrue and democratically questioning. Given that central banks sit on the extraordinary power to create money, the only limit to the central bank action is their own timidity and lack of imagination. For example, central banks could always do “helicopter money” and distribute money directly to citizens as a monetary dividend. It is undeniable that such a policy would work far more directly and effectively than QE, yet, it has been ruled out for unconvincing reasons so far.

While we agree that more expansive fiscal policies in the Eurozone (especially at the central level) would help to strengthen growth and inflation, this still is a poor excuse for central banks not to fully use their powers, for example by injecting money directly via a monetary dividend.

In fact, the view that only fiscal policy can help to reach the inflation target is oddly inconsistent with the case for central bank independence. Indeed, what is the point of granting independence to central banks if they cannot achieve their objectives… independently?

Moreover, given the recent failure of the Eurogroup to agree on a substantial fiscal capacity for the euro area, it would be more realistic from policymaker to assume that no fiscal policy will come to the rescue of the ECB. At least on the short term.

Second, we find it worrying that the ECB seems to be overlooking and downplaying the hypothesis that more fundamental phenomena may have rendered the current monetary policy powerless. Even though those hypotheses are still uncertain, the risk for the ECB to overlook them is much higher than the cost of considering them carefully, and preparing for their eventuality.

Ultimately, the credibility of the current ECB policies is eroding every time the ECB fails at lifting inflation up to its own staff forecasts. This fuels a self-fulfilling credibility problem: the less the ECB achieves its target, the fewer market participants believe the ECB can achieve its target, which in turn reduces the chances of the ECB to achieve it. There is a risk that central bankers are lagging behind the curve of economic thinking, and that they are wasting time and confidence capital by maintaining the status quo instead of looking for new solutions.

Time to review the ECB’s strategy

To be fair, the European Central Bank is not the only central bank globally that is struggling with reaching its inflation target. For example, Japan has constantly undershot its target for the past 30 years. But at least other central banks are doing something about it. Both the Bank of Canada and the US Federal Reserve are currently conducting a review of their monetary strategies, while the central banks of Sweden and New Zealand also carried one, as part of a frequent exercise.

By contrast, the last time the ECB conducted a review was 17 years ago, in 2003. More than ever, the time for reviewing the ECB’s monetary strategy is now.

The scope of such a review can and should be very broad. In our view, it should look at all aspects of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy, from the definition of the inflation target, the monetary policy instruments, the assumptions and framework of the monetary analysis and the measurement of inflation, and the communications of the central bank.

Unfortunately, the lack of progress on the reform of the European Monetary Union means the ECB will be even more overburdened when the next crisis hits and will need to resort to more unconventional policies. EU policymakers should face that reality now and push the debate on the future of monetary policy forward.

During his hearing at the European Parliament, the new ECB chief economist Philipe R. Lane said “It is a good idea to have periodic reviews of monetary policy frameworks. I am sure that the Governing Council will consider this issue in due course.” This is good news. As underlined in our recent open letter to the European Council President Donald Tusk, it is key that the next President of the ECB will be equally willing to open this debate.

However, it is critical that such re-assessment is not left to central bankers alone. Instead, it should involve other EU institutions and civil society at large. For example, the Commission and the European Parliament could create a high-level expert group to study this topic, and a public consultation could also be launched to ensure that academics and civil society can also take part in the collective reflection on the future of Europe’s most precious common good: our money system.

Image credit: anthony posey, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Economic growth = inflation which prevents tackling climate emergency. We do not need any inflation.

I agree that the institutions are more qualified and with relevant information up to date (we hope) and should control inflation as they did before the crisis however with additional tools and weapons. So institutions play an important role. The involvement of representative Citizens organisations such as Engineering, Construction, mining, retail, wholesalers, public servants, private employers, private employees, should also be drawn in the debate and offer ideas and solutions from their own perspectives deciding or recommending