The conditions are ideal for the EU’s supranational institutions to raise necessary funds for the economic recovery and green transition. The European Investment Bank has been offering a real European safe asset for some time and is likely to continue to do so, provided the accommodative monetary policy of the ECB continues.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is one of the oldest EU institutions. Established in 1958, the bank has gradually grown its influence and size, with an annual lending of around €100 billion and an overall balance sheet of around €500 billion.

The Financial Times once described it as the ‘EU’s hidden giant’.“I am sometimes surprised that political leaders are not aware what kind of instrument they have in their hands,” the EIB’s President said. Indeed, EU politicians were raging on whether the EU should issue joint debt, yet the EIB has been issuing a massive amount of bonds without any controversy.

The EIB has also grown as a key player in the fight against climate change. [1] The bank has been pioneering the issuance of green bonds, and remains by far the largest supranational issuer of green bonds in the world. In 2019, after intense pressure from NGOs, the EIB also announced an ambitious new lending policy whereby the EIB would gradually phase out its investments in fossil fuels.

Despite the EIB’s important role and the massive need to scale up green investments – estimated at €2.5 trillion by the European Commission in the next decade, there has always been resistance against increasing the EIB’s size even more. The bank itself is often insisting that its priority should be to protect its AAA rating and not engage in more risky investments. But today’s financial market reality shows a different story – one where the EIB faces virtually no constraints on its borrowing capacity.

The EIB is one of the seven international and supranational institutions in the euro area which have become eligible for the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP, or quantitative easing) of the European Central Bank (ECB), alongside other institutions such as the European Commission or the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). [2]

The EIB is one of the biggest supranationals to be eligible to the ECB’s QE programme. Since 2015, EIB bonds have represented more than 40% of the outstanding supranational debt eligible to QE. Out of a total amount of €250 billion of supranational debt purchased at the end of July 2020, the Eurosystem had bought approximately €100bn of EIB bonds.

In this blog, we want to analyse to which extent the ECB’s asset purchases have impacted the EIB’s cost of borrowing.

Losing old theories

According to conventional economics, the rate of return, or the coupon, on the bond varies depending on the duration of the life of the bond, i.e. the maturity.

With a one-year bond, the present value of the bond is less uncertain given that within one year it is more accurate to predict fluctuations in the price of the bond, as such the bond issuer puts a lower coupon on this bond.

Conversely, a ten-year bond is more sensitive to price fluctuations because of its long maturity. Therefore, considering the higher uncertainty over a 10-year period, investors demand a higher coupon to “make up” for future fluctuations.

The new reality

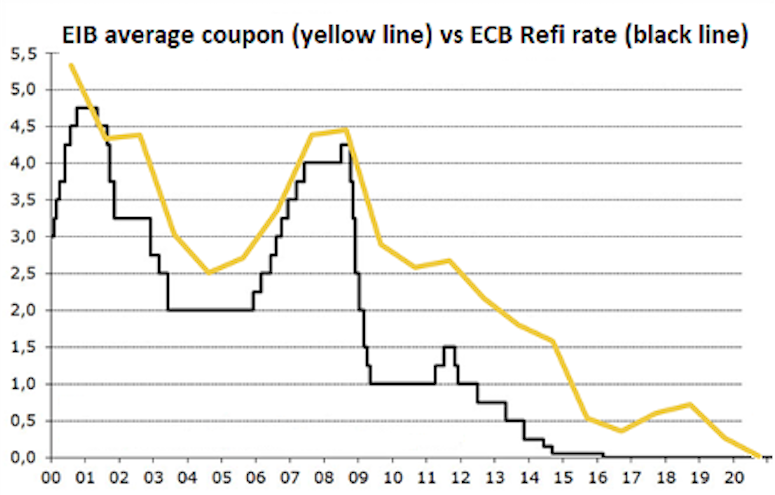

What conventional economics misses is that a lot has changed since 2012. The ECB went on an unprecedented easing of monetary policy. In the Eurozone, the refinancing rate is the central key rate at which the ECB agrees to refinance commercial banks without any limit on the amount. Figure 1 below shows that ECB key interest rates have consistently come down in tandem with the EIB average coupon.

Figure 1 makes it clear that the EIB bond yields have followed the trajectory of the ECB’s policy rate quite closely. From 2000 to 2009, the spread between the average EIB coupon and the ECB policy rate was less than 1%.

From 2009 to 2014, the spread slightly increased and was almost consistently between 1.5% and 2%.

However from 2015 – when the ECB launched its first quantitative easing programme, the spread has fell sharply below 1% again, and is converging towards 0% in 2020.

Figure 1. ECB refinancing rate (black line) and the average EIB coupon (yellow line).

Source: ECB and EIB.

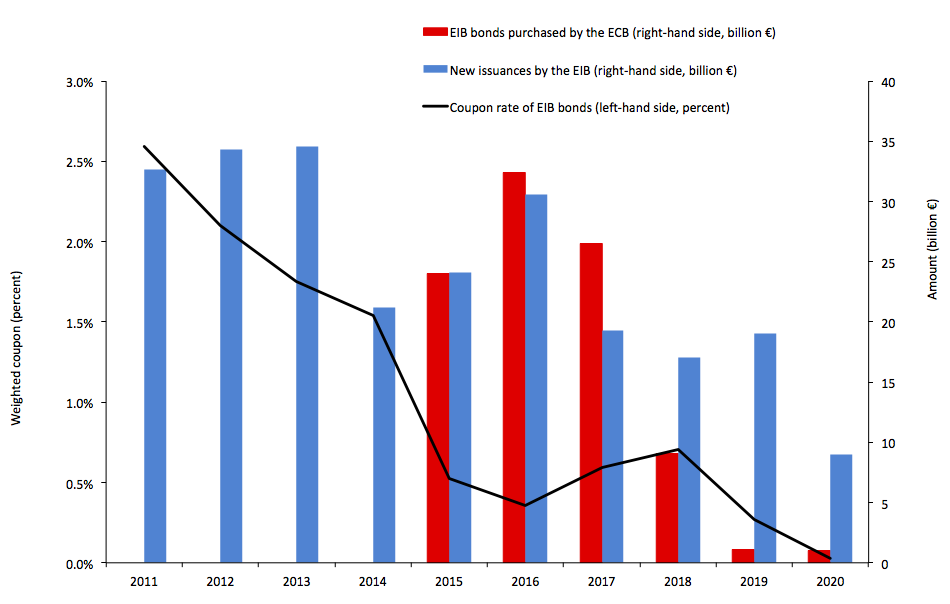

It is interesting to investigate the reason behind the closing of the spread in 2015. Figure 2 shows the amount of EIB bonds issued each year (dark blue bars), their associated average coupon (black line) and the estimated amount of EIB bonds purchased by the Eurosystem within the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) (red bars).

What the figure shows is that from 2015 to 2017, the purchase of EIB bonds by the Eurosystem was equivalent or higher than the amount of new issuances by the EIB. As such, the demand is high for EIB bonds and the Eurosystem has a high absorption capacity.

Figure 2. EIB bonds issued each year, their coupon and the amount purchased by the Eurosystem as part of the PSPP programme.

Source: ECB and EIB.

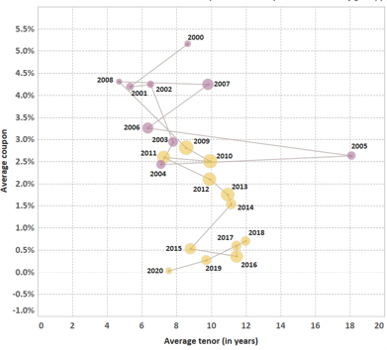

Furthermore, Figure 3 shows that both volume of issuance and average maturity are no longer predictive of coupon variations. Before the eurozone crisis, the average coupon was much higher, around 3.5%-4.0% for the average maturity of 4-10 year bonds. After the eurozone crisis, however, the average coupon has significantly fallen to below 2% at the same time as the average maturity increased to 11-12 years.

In other words, coupons rates have decreased, shifting downwards, while maturity has become longer, thus shifting rightwards. This means that the conditions are ideal for EIB bonds to increase issuance and increase maturity to benefit from low rates without spiralling the borrowing costs.

Figure 3. Relationship between average tenor, average coupon and the amount issued.

(Circles represent amount issued in € billion, purple circles correspond to 2000-08, yellow circles 2009-20)

Source: EIB investor presentation. Note: 2020 data is incomplete.

As many voices have proposed, the Eurosystem could use its QE programme to shape the market for green bonds, and boost the borrowing capacity of public investment banks such as the EIB.

Under QE rules, the Eurosystem can hold up to 50% of bonds issued by supranational institutions, compared to the national issuer limit of 33%. It is therefore conceivable that the Eurosystem could announce a new programme (e.g. Supranational Purchase Programme) which would allow the purchase of more EIB and other supranational bonds, focusing on keeping their interest rates very low or even negative. This will help enormously to fund the green transition across the Eurozone.

The ECB’s purchases of supranational bonds under QE or the PEPP programmes guarantee enough demand for bonds issued by supranational institutions, such as the European Commission.

This lesson holds true for all other types of EU borrowing. The ESM has been borrowing at negative rates for quite some time already. It is also not surprising that the recent issuance of the SURE bonds by the European Commission was oversubscribed by 13 times, at an annual coupon rate of 0.00% for the 10-year bond and 0.10% for the 20-year bond. It is also likely that the EU’s Covid-19 recovery programme, namely the Next Generation EU budget will benefit from the same windfall.

For now, monetary policy remains accommodative and it is likely to be the case for some time to come. With that in mind, there is virtually no limit to the amount of money that could be mobilised to finance sustainable investments on a very wide scale in the years and decades ahead.

[1] EIB is performing strongly with particular focus on climate related-leadership, according to E3G’s Public Bank Climate Tracker, https://www.e3g.org/matrix/.

[2] Supranational entities eligible under PSPP are Council of Europe Development Bank, European Atomic Energy Community, European Financial Stability Facility, European Stability Mechanism, European Investment Bank, European Union, Nordic Investment Bank, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/pspp.en.html.